Hello from Austria! 🇦🇹

I managed to bump into this geezer during my meanderings:

And I am writing this newsletter within earshot of the apartment where Beethoven composed his ‘Eroica’ symphony. Will this email have similar resonance down the ages?

Time will tell, but yes.

Holiday is also a time to reflect. I’ve been reflecting on hi, tech.’s editorial direction, naturally.

As a one-person, semi-regular, fee-free newsletter, hi, tech. covers an awful lot of ground. This has its benefits, for sure: I can write about whatever catches my eye each week, so long as it has some relevance - however tissue-thin - to technology.

But where benefits are to be found, can detriments be far behind? Alas, no. This freewheelin’ style makes it trickier to pitch the newsletter to new readers, some of whom sign up thinking they’ll get quick-win bullet-points or dry business analysis. Imagine their disappointment.

So in general, there are three broad areas I cover:

Big Tech: The latest stories on the tech giants, with a focus on their long-term business strategies.

This often means US-based big tech, but not always. For example, this week we’re looking at China’s big tech companies.

I’ll typically put data analyses of consumer/business trends in here.

Marketing: I mostly look at data privacy, AdTech, and new product launches.

I’m not too interested in “marketing best practice” lists and the like for this newsletter, but I can point people in the direction of those resources when desired. I do get requests to create this sort of thing, but I cover that on other blogs.

Emerging Technologies: These are perhaps my favourite stories, where we cast an eye over wacky new trends and try to make some sense of them. I’ll try to pin down what the business model is, whether the market really wants these new innovations, and how they will impact existing businesses.

And if you’re new to the newsletter:

Welcome!

Sign up here 👇

📽 YouTube is reportedly planning to launch a 'channel store' for streaming services

The story: YouTube is building a new store for paid subscriptions to individual channels and it is in discussions with launch partners.

Why it matters: YouTube already offers streaming bundles with add-ons. This new approach opens the possiblity of subscriptions to select channels, without the need to buy a cable-style bundle. That would set YouTube apart from both cable networks and streaming platforms like Netflix.

🔎 Google Search is changing, in a big way

The story: Google has announced that it will make sweeping changes to its search algorithm. It hopes these changes will improve “user satisfaction” and reduce the quantity of “SEO content” that is designed to generate clicks.

Why it matters: Most companies will notice some volatility in their search rankings over the coming weeks. Those that already focus on helping searchers complete a task with their content will likely benefit.

I tried so hard to help people with this in early 2019. See the presentation here.

🍏 Apple asked for a cut of Facebook’s ad sales years before it stifled Facebook’s ad sales

The story: Apple and Facebook had a secretive discussion about this, at Apple’s request. Facebook said no and might now be wishing it answered otherwise.

Why it matters: Meta blamed Apple’s new privacy measures for a $10 billion drop in Facebook ad revenues earlier this year.

Apple is investing heavily in its own advertising technology and will soon launch ads in Maps, Podcasts, and a whole load of other first-party apps.

🤖 Cognizant Machines: A What Is Not A Who

This excellent article discusses the key challenges in the pursuit of “general AI”, and it explains why programs like GPT-3 and DALL-E 2 are such significant steps forward.

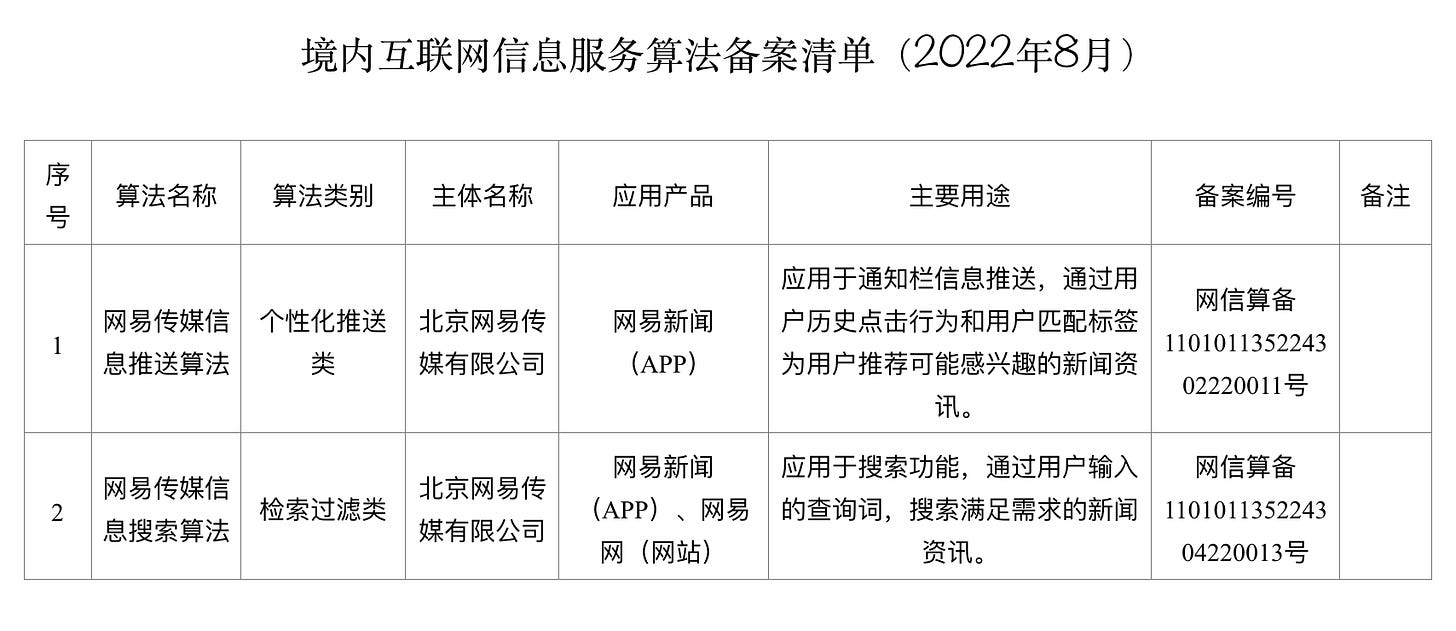

China is investigating the big tech algorithms

What happened? China’s data watchdog (the Cyberspace Administration of China, or CAC) released a list of 30 algorithms that have been submitted for analysis by the country’s biggest technology firms, including Alibaba and ByteDance. This comes after the Chinese government passed new regulations that compel the tech giants to agree to greater oversight.

CAC requires these companies to submit to “a self-appraisal on the security of the algorithms, the data they collect, whether that encompasses sensitive biometric or identity information, and what data sources are used to train algorithms.” This week’s movements open the possibility of CAC conducting its own assessment of the inner workings of these companies.

The summary list of algorithms that CAC released is intended for public reading and as such, it provides little more than a description of what the companies do. For instance, it says that the Weibo recommendation system promotes “Weibo content that users may be interested in through the user’s historical browsing behavior.” So yeah, you already knew that, but that’s not the real story here.

But then, what is the story?

We do indeed know that Douyin (TikTok’s sister app in China, also owned by ByteDance) takes user data to feed a recommender system. What we don’t know is how exactly it uses that data to match users with specific videos - or even the full list of data sources it uses, nevermind the assumptions its systems make about user preferences.

This latest development won’t make us any the wiser as casual observers, yet it will allow the government to assess how these platforms make automated decisions. No doubt, they will have a lot of questions and may even bring in engineers to ask how they made decisions when coding the algorithms. I would offer that we’ll be able to infer CAC’s conclusions from their subsequent regulatory actions.

Naturally, the tech companies would never make such submissions of their own free will. They will also try to conceal their most closely guarded business secrets, as Meta has successfully done in the US when pressed to submit its algorithms for examination.

However, the real story here is about the relationships between business and government in the world’s biggest economies. Both China and the US are taking a closer look at social media networks, albeit with (I would argue) divergent intentions.

Right-oh, so why is China doing this?

Officially, because there have been “data abuses” by the tech companies. CAC has given out targeted fines to firms for data privacy breaches, for example the $1.2 billion fine to ride-hailing app DiDi earlier this year, but this action looks somewhat different. It is a much broader attempt to understand and then reshape the relationship between technology services and consumers. The EU and the US are asking similar questions, without going so far in the search for answers.

Off the record, there’s a strong chance that China has noted the pernicious effect of social media in western countries. More specifically, it will have realised that these social networks can shape political opinion and therefore leave the population open to manipulation by external forces. You can imagine why China’s one-party state wants to keep that in check.

And if the Chinese state understood how these algorithms worked, just imagine how powerful their propaganda could become. The application of that knowledge would be two-fold:

Keeping their own country in check. China can push its own messaging, exclude dissenting voices, and also increase the state’s leverage over the tech sector.

Weaponising social media in foreign states. With access to sensitive information about the operating logic of big tech algorithms, China could shape trends and narratives beyond its own shores.

China is already working on such initiatives. Buzzfeed reported just a few months ago that:

“Four former ByteDance employees, each of whom worked on [US-based news app] TopBuzz, claimed that ByteDance instructed members of its staff to place specific pieces of pro-China messaging in the app.”

The TopBuzz plan is almost amateurish in its simplicity.

Of course, China could instead use social media to sow even more division in western nations, not that there’s much of that currency left.

This could sound scary and perhaps it should, although it is simply the nature of foreign policy over the course of the past century. Justin Hart writes in Empire of Ideas: The Origins of Public Diplomacy and the Transformation of U. S. Foreign Policy that the US State Department used musicians including Louis Armstrong as propaganda tools in the 1960s. The US sponsored Armstrong’s 1960 tour of Africa to promote the country’s image abroad and then, unbeknown to Armstrong, CIA spies used this access to uncover secrets about local leaders.

The 2022 equivalent would likely involve TikTok.

ByteDance assures regulators that TikTok is now an entirely separate company with its headquarters in Singapore and minimal input from Beijing. TikTok has moved its operations to Oracle’s cloud servers and has now asked Oracle to audit the algorithms it uses to recommend content.

The US remains highly sceptical about these claims and many politicians are concerned that their citizens’ data can still be viewed by ByteDance employees.

European Union states have recently ruled that EU citizens’ data cannot be sent to the US for processing by Google, so it seems unlikely they will approve of EU data moving to ByteDance’s servers - when that case eventually gets to court.

Yet China has learned valuable lessons from the United States’ dominance of popular culture in the 20th century. It will play along with the theatre of state/business separation, in the interests of the country’s longer-term ambitions.

Facebook tapped into phenomenal growth with its social graph; the next phase of social media belongs to TikTok’s content graph.

Why is China doing this now?

China likes to keep control of censorship, but that is increasingly elusive in a world of opaque algorithms, livestream content, and instant interactions. Although we may have already passed the tipping point in this regard, the state wants to take action before it is certainly too late. China can wield this power in a way the US could, but will likely choose not to.

As mentioned, the social networks are all shifting their focus away from social graphs that connect us to our friends’ content, and towards TikTok-style feeds that surface content for us from anywhere in the world, based on its predicted likelihood of keeping us in the app. The core idea is to keep us hooked, by whatever means necessary. Everyone from Facebook to Twitter and even Amazon is now trying to copy TikTok.

A leak earlier this year revealed that TikTok shares an internal document called “TikTok Algo 101” with select departments. Once more, it does not reveal any significant secrets, yet it does give an overview of the company’s aims:

“The company’s “ultimate goal” is growing daily active users by increasing user retention rates and total time spent each time TikTok is opened.

Each video is scored by the number of likes, comments and playtime. There’s even a handy formula for success, according to the document: Plike X Vlike + Pcomment X Vcomment + Eplaytime X Vplaytime + Pplay X Vplay.”

In such a formula, just “being famous” is no longer a guarantee of social media interaction. Anyone can go viral if they create content that partially satisfies the desires of an audience segment. That makes the app addictive for content creators, as well as consumers.

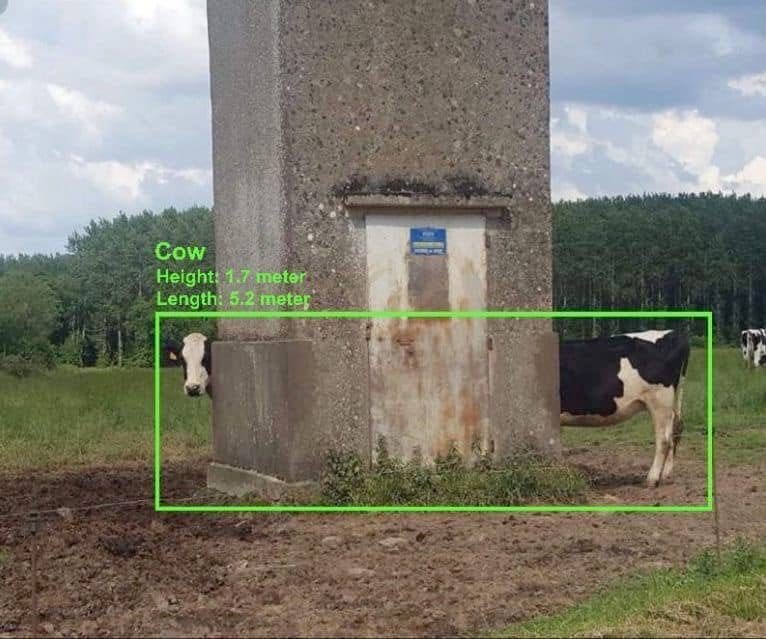

In a system where we all compete to capture attention, where “quality” is in the eye of the end user and quantity is a neccessary means to that loosely defined end, who better to create the content than an AI program? Brands in China are increasingly turning to virtual influencers for their livestream shopping feeds, since they can easily create a new avatar to serve every micro-segment of the audience. With the right data inputs, this technology could produce endless variations on content themes and trends, which the algorithm would immediately serve to the right users.

A report by the media monitoring group Media Matters for America found that TikTok “sends users spiraling down a "rabbit hole" of increasingly further right, extremist content”, sometimes starting with fitness videos and slowly surfacing more and more radical viewpoints. There is little reason to believe that the algorithms are written with that intention in mind, which is why regulation is so necessary.

However, there are differing opinions on how best to protect users.

There is a school of thought that as long as the outcomes are aligned with the inputs, all is well. That is to say, if people consent to share their data with a platform and then they are happy with the results of the data sharing, that is generally fine. They ordered the hot dog, they liked the taste, who cares what happened in between?

The tech firms will hold this line to preserve their own IP, for as long as possible. The firms will agree to some oversight, perhaps from an external board of their choosing. We know already that this will be insufficient, because the very same tech firms need maximum engagement to feed their ad platforms.

Therefore, when we ask whether the US and EU should follow China’s path, we must focus on our desired outcome and work backwards. It is unclear if seeing more details from the tech giants will give the state the deep knowledge it needs to design effective reforms.

I am reminded of an excellent Twitter thread by the former CEO of Reddit about the impossibility of removing disinformation on the platform. Every well-intentioned policy bred a dozen new problems.

Loath though I am to use the term, a challenge this pervasive requires a “holistic” solution. It is about psychology, behavioural science, socioeconomics, and politics - as well as statistics, platform design, artificial intelligence, and data management.

There is excellent work already in each of these fields, but who brings them together into a convergent solution? To tweak the algorithm is to use a scalpel when only an axe will suffice.

In some regards, the intentions of both China and the US on this front are coaxial. They both want to keep the big tech companies on a tighter leash and they want to maintain some control over the content their populations see. The means of arriving at that point will be distinct, because the finer details of each state’s intentions are so divergent.

The US should follow China’s lead in one area: the latter is taking proactive steps towards its own goals. Given how pernicious some of those goals might be, this should be all the more reason for the US to get into gear.

Algorithms are critical to the functioning - both positive and negative - of social networks. Nonetheless, they are not “evil”; any malevolence comes from outside, and effective regulation will take the entirety of this system into account. Taking a peek at the algorithms is only a start.