Hello,

Cynics will wonder why anyone should pay for a newsletter when generative AI can supposedly do everything, for free.

But you don’t get this from your robo-assistants:

I was wondering the other day, has there ever been a worse pun than Veganuary?

You know the idea: people “go vegan” for a month and then go back to eating meat.

The stress falls on the first, elongated syllable in ‘vegan’ - /ˈviːɡən/ or VEE + guhn.

The stress falls on the first syllable in ‘January’ - /ˈd͡ʒæn.j(ʊ.)ə.ɹi/ or JAN + you + air + ee.

If you maintain the structural integrity of the word ‘vegan’ and merge it with ‘January’, you would get:

VEE + guhn + you + air + ee

On the other hand, if you give greater weight to the original ‘January’, you have to truncate the first syllable in ‘vegan’. It results in:

vuh + JAN + you + air + ee

Neither works and yet we all go about our business as if they do.

How about these alternatives?

Jamuary: Eat jam for a month

Panuary: Eat only Spanish bread

Tanuary: Go to the Maldives

Scanuary: Get every possible medical checkup

Chanuary: Watch a Jackie Chan movie every day for a month

Janstewary: Eat stew

These are all much more fun and they’re built on a functional pun.

AI is all the worse for its lack of whimsical meanderings, if you ask me.

We are here, of course, to discuss generative AI (again). Two articles intrigued me this week:

Companies can ‘hire’ a virtual person for about $14k a year in China: Baidu is building and selling virtual influencers for tidy sums. At the cheaper end of the scale, it sells virtual customer service support staff. At the more expensive end, it creates influencers that can represent brands.

China is building a parallel generative AI universe: This excellent article from TechCrunch dives into the weird world of China’s OpenAI equivalents.

I took a look at the latter in more detail below.

The quick summary:

Baidu and Tencent offer text-to-image tools that generate images based on a text prompt, just like DALL-E 2.

Tencent's tool, Different Dimension Me, turns any photo of a person into an anime character, but access has been blocked to foreigners due to a surge in traffic.

Baidu's tool, ERNIE-ViLG, is slightly less effective than DALL-E 2 in the hi, tech. test.

People in China are using these tools to create content for social media and make money through ad revenues.

China has already regulated the use of generative AI, with the Cyberspace Administration of China banning the creation or distribution of "unhealthy or distorted" content and requiring companies to report any illegal use of AI to authorities.

First, let’s assess the main tools.

How can you try Chinese generative AI?

ERNIE-ViLG: This is a Baidu text-to-image demo and it’s the one I’ve spent most time trialling.

Different Dimension Me: A tool from Tencent that turns any photo of a person into an anime character.

Unfortunately, Tencent has blocked access to foreigners after a surge in traffic last week.

Taiyi: This text-to-image tool comes from the IDEA lab, led by the former head of Microsoft’s research lab in APAC.

How well does Chinese generative AI work?

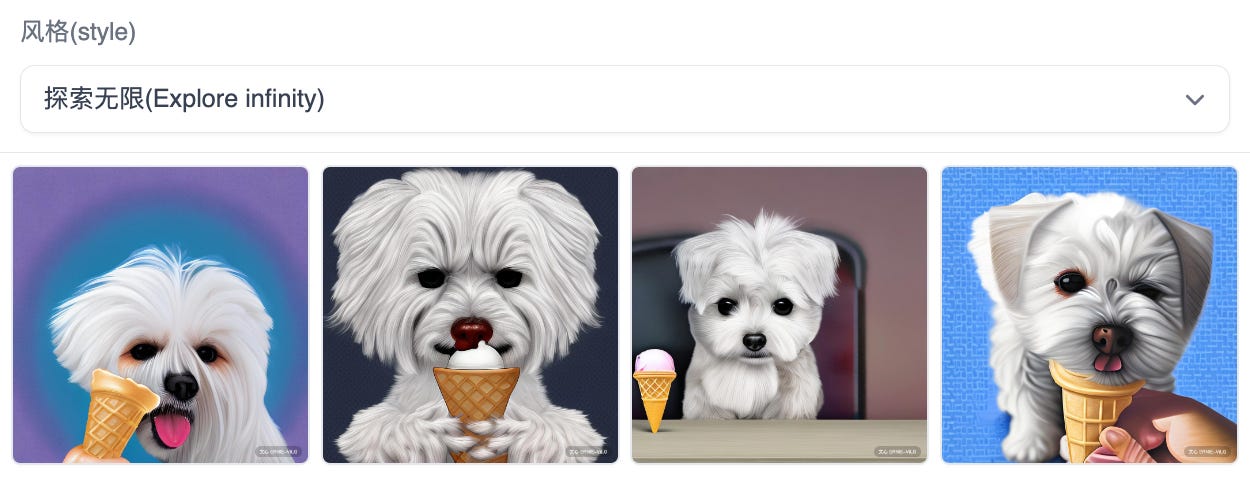

Let’s try the Baidu tool with this prompt first:

纽约市一只吃冰淇淋的马耳他狗,数字艺术

Or, if you for some reason do not speak Chinese:

A maltese dog eating an ice cream in New York City, digital art

Here’s what Baidu gave me:

They’re good, they’re cute, and the third one looks like he could be in a Wall Street boardroom.

The second one could even be a baddie in one of the Spiderman movies, which are famously set in Manhattan. He’s scheming to turn the sprinklers on any time a cat enters his garden.

However, they aren’t really eating the ice cream and the NYC references are oblique, at the very best.

Baidu Score: B-

Room for improvement, then.

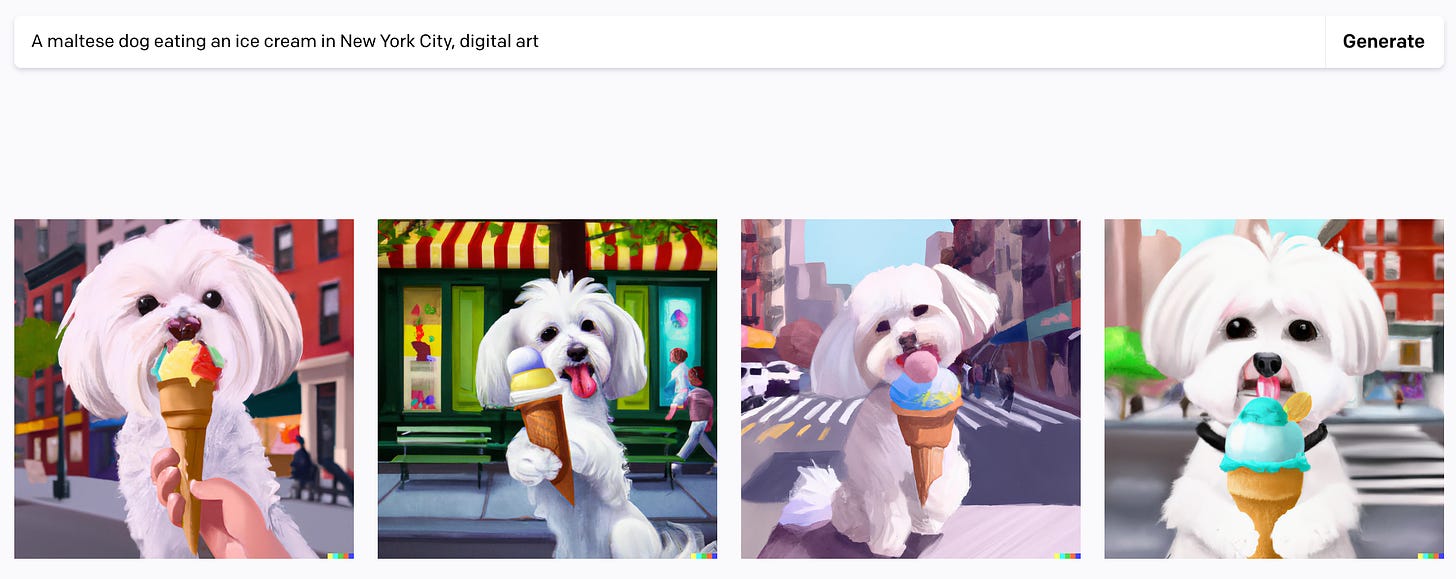

Let’s try DALL-E 2 with the same prompt:

It nails it. Cute, eating the ice cream with aplomb, and it’s unmistakeably NYC.

DALL-E Score: A

But maybe my prompt is the problem? Perhaps my Chinese (or Google Translate’s Chinese…) is not as good as I thought?

Well, let’s try another one:

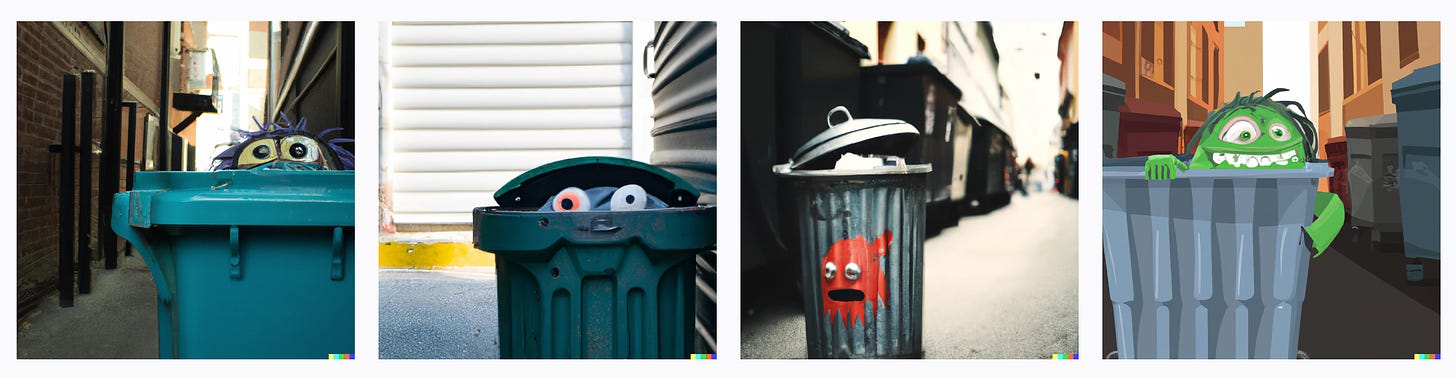

躲在小巷垃圾桶里的可爱怪物

(A cute monster hiding in a garbage can in an alley)

Here is the Baidu effort:

This is better, no? The monsters are cute, they’re definitely hiding, and that’s an alley if you ask me. They do lack a certain expressive elan in their faces, however.

Baidu Score: A-

And now DALL-E:

There is greater variation here, which I can appreciate. The fourth one is perhaps more maniacal than cute, but he’s a monster after all. I chose this one to challenge them.

The third one is “in” the bin in the sense that he has merged with it like some sort of nightmareish, “Binman” supervillain.

DALL-E Score: A-

How are people in China using generative AI?

On the whole, they are doing what everyone else is doing. They’re making cool and/or insane content and sharing it on social media.

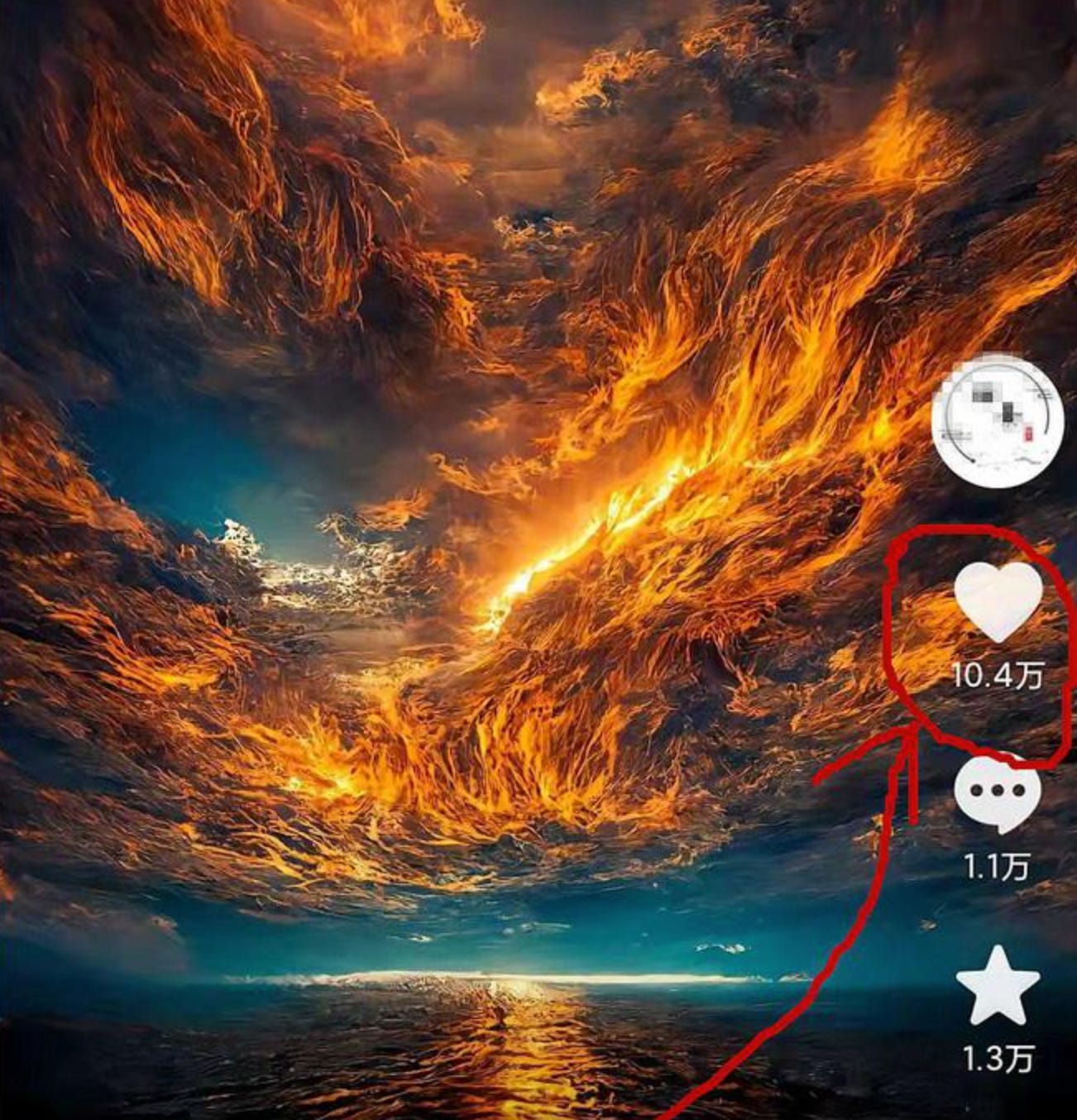

I also stumbled upon a post by a Chinese blogger on Weixin (WeChat, basically) who was sharing ways to make money with generative AI. They posted some of the images that had generated the greatest interaction and, therefore, money.

The user boasts of making hundreds of dollars per post by sharing carousels of AI-generated images like the one above. They broke down the ad revenues one can expect for a post, based on the number of views, likes, and comments, along with tips for writing prompts in the generative AI interfaces.

As a result, one can imagine Chinese social media might soon be flooded with these images.

Is China planning to regulate generative AI?

It already did. In fact, way back in February 2022 (which is aeons ago in AI terms now) China released a series of restrictions for these then-upcoming technologies.

See, China’s AI regulation is centralised and proactive. The country has initiated a number of new departments to oversee the development and use of AI.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) already banned the publishing and distribution of "fake news" created by an AI, too. This doesn’t work (the onus is on publishers to stem the flow), but the intention is there.

The new legislation states that:

Media that is created without the subject's permission is also forbidden, as well as anything that goes against the national interest.

The “national interest”. Indeed. 🤨

It defines generative AI as:

"technology that uses deep learning, virtual reality, and other synthesis algorithms to generate text, images, audio, video, and virtual scenes."

That means generative AI tools are already censored in China. There is a lengthy list of keywords that one simply cannot use.

If China’s generative AI tools can only respond to certain prompts and their results are restricted, that must also dictate the training data they use.

I referenced Different Dimension Me earlier in this post. It takes an image of a person and turns it into an anime character. It was very popular in Latin America, but users there quickly found out that if they entered an image of a black person the tool returned highly offensive results. Of course, the tool was only trained using images of Asian people.

We see just how quickly these technologies become political tools of control.

How is the US approaching generative AI legislation?

Joe Biden’s government has just released its non-binding “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights”.

It has five general, well-meaning principles:

The Blueprint is a step in the right direction and it asks all the right questions, but it has no teeth. These are advisory principles that companies should consider, not mandatory rules.

Although the US has been slow to move on national legislation, it has imposed some significant sanctions internationally.

The chips are down in China

See, China will have to develop its own computer chips to power the next age of AI. The US has placed a ban on the export of high-end chips to China, as of September 2022.

Baidu does not believe this will hinder its progress in the immediate short term, as its technology does not use the latest chips. Its head of AI also says they already have enough Nvidia chips on hand to see them through.

In the medium- and long-term, Baidu expects to have access to Chinese chips that will match or better what the US develops. It says it already runs large language models using its own Kunlun chips, too.

In truth, no-one knows if China will indeed develop world-leading chips and it would hardly serve Baidu’s interests to be pessimistic. It has no choice, anyway.

What impact will this have on generative AI?

I’d expect the above to have a significant impact on how generative AI evolves in China and elsewhere.

Within China’s borders, it will be trained on restricted data and its use cases will be closely monitored.

The strange thing is that these very restrictions can be an aid to creativity. In the West, we have a general sense that this technology could revolutionise “everything”. In China, the enforced constraints can help narrow the focus to more specific, everyday uses for AI.

Nonetheless, it is impossible to ignore the conclusion that the centralised political culture in China will act as a handbrake on innovation. I have compared China with the US to provide a point of comparison, but the reality is that US researchers collaborate freely with peers from around the world.

This will naturally lead to improvements in the technologies developed by US companies, as will the free flow of data across international borders. The Western world also has an advantage in the development of advanced processing.

No government has figured out the best way to regulate new technologies. We can already see that generative AI could have a negative impact on society and it is understandable that China should be wary of the rapid pace of change.

Although China will not want to be left behind, its cautious approach to generative AI means it is unlikely to take the lead in this field.